Georgian Greetings from Soho House this Christmas

In 1644, only a century before Soho House was built, Oliver Cromwell banned Christmas! Carols were forbidden and anyone caught cooking a goose or baking a Christmas cake or boiling a pudding was in danger of fine, confiscation or worse.

By the 1800s it was once again a time of celebration, having been reinstated by Charles II. The Georgian Christmas season began on 6th of December (St. Nicholas Day). Gifts would be exchanged both then and on New Years Day and the main feasting occasion was 6th of January (Twelfth Night, Epiphany). St Stephen’s Day was 26th of December and is now better known as Boxing Day as this was when servants would be presented with gifts and donations made to charity.

The gentry spent the Christmas season in their country houses and didn’t return to their London addresses until February. It was a time of high celebration with gift and charity giving, balls, parties, games, gifts and lots of food. As families were already gathered together it was also an opportunity for weddings.

The Georgian Christmas menu would have included soup, turkey, goose, duck, and cheese. Mince pies have been eaten at Christmas in England since the sixteenth century, however they were made of minced meat. Only later was this replaced with dried fruit and spices. During this period Christmas pudding was better known as lum pottage.

The star of the show would have been Twelfth Cake, a version of present day Christmas cake. It was sliced and given to all members of the household including servants and guests. It contained a dried bean and a dried pea. The person whose slice contained the bean was King for the night; a slice with a pea indicated the Queen. Whoever won, regardless of their social standing and position in the household, was recognized by everyone as the evening’s King and Queen. By the Regency period, Twelfth cake became elaborate with added icing, trimmings, and figurines and it remained popular until the late Victorian period.

Decorating the home with holly, evergreens and mistletoe was well established and practiced throughout the Georgian period, however the Christmas tree was a tradition not yet adopted. It is widely believed that Queen Victoria is responsible for the popularity of the Christmas tree, as a tree would be placed in her bedroom each Christmas. After Victoria’s marriage in 1840 to Germany’s Prince Albert, it grew in popularity amongst the middle classes after the British press reported on the trees adorning Windsor Castle. However, it was George III’s wife, Queen Charlotte, who brought the first version of the present day Christmas tree to Britain in 1800. She had it decorated it with gifts, dolls and tapers after her German traditions.

The yule log was chosen for the fire on Christmas Eve. Wrapped in hazel twigs and dragged home it was the centre piece and would burn in the fireplace during the Christmas season. Traditionally a piece would be kept back for the following year.

As part of the season’s celebrations British Pantomime grew in popularity during the Georgian period, particularly among the upper classes. Carols as we understand them didn’t exist although some such as ‘While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks at Nights’, ‘Joy to the World’ and ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing’ were beginning to gain in popularity.

Entrance hall of Soho House and portrait of Matthew Boulton decorated with evergreen made by Asian women’s Textile Group and Soho House Volunteers.

This Christmas there are festive tours of Soho House which offer the rare opportunity to see the House decorated for a Georgian Christmas and to hear tales of how the season was celebrated over two hundred years ago (for details visit: http://www.bmag.org.uk/events). There is also a special evening at Soho on 13th December where there will be carols and readings, followed by an opportunity to look around the historic House decorated for Christmas with a choir singing in the world famous Lunar Room (for details of this event visit: http://www.bmag.org.uk/events?id=3501.)

Louise Deakin,

Visitor Services Assistant

A Lot of Hot Air

Apart from being one of the most striking architectural features, the gas lights that hang over the Industrial Gallery are an important reminder of the Museum’s roots. They are beautiful to look at and vital to telling the story of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. However, they are also mysterious and we are still trying to find out exactly how they functioned.

This picture shows the Gas lights above the Industrial Gallery during the 1960s. During this period they were not visible from the gallery.

The gas lights have a number of different names. The term ‘Gasoliers’ comes from French ‘chandelier’ and is frequently used in literature about the museum. However, my favourite name is ‘Sun-Light Burners’. This was used to describe them in the minutes made at meetings about opening a gallery. Apart from being vaguely poetic I prefer this term because it accurately reflects their job.

There are seven gas lights in total. Two in the Edwardian Tea Room, three in the Industrial Gallery, one in the Round Room and one above the Vestibule reception area (in every room of the original gallery). They were manufactured by Messrs. Strode and Company from London for the cost of £488.

This is the lamp above the Round Room. I imagine this lamp in particular would have looked like the sun when lit.

The purpose of having gas lights was revolutionary. It reinforces the argument I made in my previous blog entry about how Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery was an institution designed by the people and for the people. In the 1880s Art Galleries were the domain of the middle classes. As well as being a place to see beautiful objects they were also a place to be seen by your peers. Because museums were lit only by sunlight they were only worth visiting during daylight hours. Working class people, generally, did not finish work until the evening and therefore would not be able to see the exhibits.

By providing gas lights Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery enabled these people to view the exhibits too. This explains why the term ‘Sun-Light Burners’ applies so well. The Museum was established specifically to inspire the artisans, therefore it would have been a huge mistake if they could not view the things specifically displayed to inspire them.

When the gallery opened in 1885 it was on top of the newly municipalised city gas offices. Nowadays there are only two things to remind us of this: the Foundation Stone in the main entrance and the gas lamps.

So the practical considerations: how were these lights lit? Naively, when I first considered this question I imagined a Victorian man leaning over the iron work on the balcony of the Industrial Gallery with a large wooden stick, prodding the lamp from a distance and hoping for the best. Obviously, this was not the case. In the case of the lamps above the Vestibule and Round Room, they were winched down to a gentleman below who would light it, shout up to say it was ready, and then be winched up again very early in the morning. It is clear to see that the entire structure would have moved because today they are hidden away in the ceilings. When stood in the roof space this sort of movement is also evident from the design of the lamps themselves.

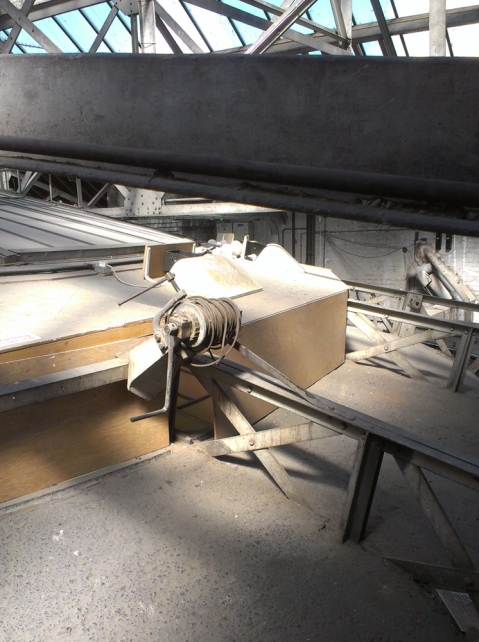

This shows the mechanism used to winch the lamps down so they could be lit.

For the lamps above the Edwardian Tea Room and Industrial Gallery the procedure less obvious. There are winching mechanisms in the roof space but the outer structure of the lamps is clearly static. I am currently waiting to see the original blue prints, which will reveal the procedure but at the moment my best guess is that an internal part was winched down to the floor where it was lit and then brought back up.

The one question we, as Visitor Assistants, always get asked is ‘do they work?’ As the lamps used Town Gas, which is no longer used, it is impossible to tell. Also there are a plethora of conservation issues connected to having gas lamps and oil paintings in immediate proximity so it is probably for the best that we don’t use them today!

So the importance of these architectural features is huge. They remind us of the connection to the gas offices. They are a visual symbol of the equalising effect Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery had on the cities communities when it opened. They also fill everyone who sees them with curiosity and invite questions that we still cannot fully answer.

Olivia Bruton

Visitor Assistant,

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Bostin Austen at Soho House

Now in it’s third year, Jane Austen Day is celebrated each summer at Soho House museum and this year’s celebration took place just over a week ago. Although Austen herself never visited Boulton’s home, the Georgian property provides the perfect setting to bring the world of her novels to life.

Austen was a novelist whose works earned her a place as one of the most widely read writers in English literature. Georgian society is the backdrop of all of Austen’s novels. Set during the reign of George III, they describe everyday lives, social hierarchies, gender roles, marriage, and the pastimes of well-off families. They provide an insight to the English society of this period.

Austen lived her entire life as part of a close-knit family located on the lower fringes of the English landed gentry. The support of her family was critical to her development as a professional writer. Her father was a clergyman and after his death, she, her mother and unmarried sister Casandra went to live in a cottage on her brother’s estate. Cassandra was Austen’s closest friend and confidante throughout her life. It was in these later years Austen successfully published four novels which were generaly well-received: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park and Emma. These works were published anonymously and brought her little personal fame. Austen’s most famous work remains Pride and Prejudice. In this novel her most beloved heroine Elizabeth Bennet must navigate the complexities of life as a young woman of limited dowry. During Jane Austen Day Pattern 23 performed famous scenes from Austen’s books, including Mr. Collins ill conceived marriage proposal to Elizabeth.

When Jane Austen’s characters talk about buying a dress, it means in fact that they are going to buy the necessary fabric, which they will then give to a dressmaker who will make a dress to their specifications. Patterns for dresses in the latest London fashion were found in all the women’s fashion newspapers. In ‘Emma’ Harriet Smith buys muslin cloth with this intention. For Jane Austen Day I asked a friend to make a Regency gown for me to wear. During the day there were also period hair and make-up demonstrations carried out by Julie Stevens.

Austen’s plots, though fundamentally comic, highlight the dependence of women on marriage to secure social standing and economic security. A woman would have belonged in the first instance to her father and later her husband. She would have been legally subordinate to him, without rights and would not even have even been able to choose where she lived.

All members of the Lunar Society, who regularly met at Soho House, were committed to the idea of education, but what that meant for daughters and wives tended to be different from what it meant for sons. The subjects both Jane Austen and Matthew Boulton’s only daughter, Anne studied formed the main elements of the typical middle-class young woman’s curriculum. While away at school, Anne studied English, French, drawing, history and geography. Later, she learnt music from a Mr Harris in Birmingham, botany from Boulton’s friend Dr William Withering, and embroidery from Mary Linwood, a celebrated embroiderer of so-called ‘needle paintings’. Austen has been described by biographers as an accomplished seamstress and was very fond of dancing. These education topics were highlighted during Austen Day, with embroidery and dancing demonstrations for visitors to take part in.

Jane Austen acquired the remainder of her education by reading books, guided by her father and her brothers and had unlimited access both to her father’s library and that of her uncle. Like all gentry of the day, letter writing was a favoured and necessary past-time. In an uncharacteristic letter, the usually kind Anne Boulton is scathing about an expected visitor (in tone similar to Austen’s much-loved character Emma Woodhouse):

‘She is neither young, or handsome, has what some people call a pleasing cast with one eye, talks a great deal and would be glad to be thought young, notwithstanding wrinkles and grey hair begin to appear, but with all these perfections and imperfections she is I am told a sensible and entertaining woman.’

Unlike Austen, Anne was not dependent on the kindness and charity of her brother and relations after the death of her father in 1809. Boulton laid his plans well: ‘I propose to set apart, in my lifetime, as much money, land, stock or good securities as will be sufficient to support my daughter handsomely and comfortable’

Boulton left Anne a combined fortune of £34,000, enabling her to move from Soho in 1818 to a house of her own after her brother married. At Thornhill she kept a very comfortable but modest home. Upon her death in 1829 she left each of her servants one years wages, plus a further £20 each for the two longest-serving. Land she had purchased and the remainder of her fortune she left to ‘my dear brother to whom I now bid a long and last farewell.’

Jane Austen continues to be a huge influence on popular culture and this year’s celebration at Soho House was a great success. Staff, volunteers and visitors had fun immersing themselves in Austen’s stories, etiquette, interests and wit.

Louise Deakin,

Visitor Services Assistant,

Soho House

Quotes: The Hardware Man’s Daughter by Shena Mason, published by Phillimore & Co Ltd, 2005.

Volunteer Week Celebration

I have a true penchant for our magnificent city of Birmingham. Even after travelling the world and experiencing the splendour of the South Pacific, Europe and Caribbean I still found my true heart was back in Brum.

Birmingham has so many wonders to be experienced, from our diverse cultural quarters, our proud industrial legacy, our deeply engraved historical heritage, our numerous parklands, our copious canal system, our vibrant social and culinary scene and of course our beloved and cherished museums and art galleries.

I am not the only one with a love for Birmingham though. There are a dedicated group of individuals who unite in their passion for Birmingham and they give up their precious time and resources to volunteer for the various sites of Birmingham Museums Trust (BMT). This band of devoted and fervent volunteers create memorable moments for visitors at BMT sites and they instil a new pride in the city of Birmingham. These volunteers do this selflessly out of enthusiasm and desire for the legacy and future of Birmingham; they ask for nothing in return but the satisfaction that they are making a true difference to the city’s prospects, success and its heritage.

So when Alex Nicholson-Evans (Volunteer Development Officer at Birmingham Museums) decided to formally recognise all the volunteers of Birmingham Museums during National Volunteer Week and celebrate their contribution, it was a real honour.

Some of the Birmingham Museum Trust volunteers

We were truly treated and indulged to a full tour of Aston Hall, even areas not visited by the public, by Barbara Nomikos (Property Supervisor at Aston Hall) whose knowledge and enthusiasm for the house and resident families was sincerely inspirational, compelling and exhaustive. The indulgence continued with a magnificent picnic washed down with lashings of Pimms! Alas, the event had been planned as a picnic on the lawn but the UK weather had other plans and an onslaught of good old British rain, saw us camped out above the newly renovated stable block. However the weather could not dampen out valiant volunteering spirits and a fabulous time was had by all. To round of such a spectacular day we were subjected to, sorry enjoyed, an amusing and entertaining quiz! All in all a wonderfully memorable and very appreciated day.

So I would like to thank Alex, Rachel, Barbara, the team at Aston Hall and all the volunteers who attended in making us all feel so valued and appreciated. Although we volunteer out of love and passion, this kind of recognition is greatly respected and continues to fire our hunger and desire for volunteering.

Thanks to the dedication of people like Alex who make us all feel special and appreciated, we will keep on standing side by side and continue our volunteer work, ensuring we uphold and endorse Birmingham as the truly magnificent city it is.

Phil Mellanby,

Volunteer

For more information about volunteering or to be added to our volunteer list visit: bmag.org.uk/support-us/volunteer

Curator Spot! Henrietta Lockhart talks about ‘Christ as the Man of Sorrows’ – artist Petrus Christus

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery curator Henrietta Lockhart talks about ‘Christ as the Man of Sorrows’ by the artist Petrus Christus. This tiny panel dates from circa 1450. It would have been used to aid private prayer.

Watch a subtitled version of the video on Youtube.