Thank you to our volunteers!

We are lucky at Birmingham Museums to have hundreds of volunteers support us each year. By the end of 2014 we will have had the help of over 600 volunteers! As the Volunteer Development Officer I feel incredibly lucky to work with such talented people and as an organisation we are so grateful for the generosity of our volunteer team!

Some volunteers join us for a day, like our fantastic Experts who run our Meet the Expert Days at Thinktank, inspiring the scientists of the future. Others are with us each week running guided tours, documenting our collections, working on conservation projects and much much more. You can read about many of our volunteers’ personal experiences through this blog.

So it was a real pleasure for us to host over 100 of our volunteers on 10th December at our annual Thank You party.

This year the event took place in our newly refurbished Edwardian Tea rooms at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. For us, this event is a chance for us to thank our team for all that they have done over the course of the year, but also a lovely opportunity to bring together volunteers from across all nine of our museums.

We had some lovely speeches of thanks from Ellen McAdam, Director of Birmingham Museums and Simon Cane, Deputy Director, and a fantastic team of 15 members of staff volunteered to make sure our team were well looked after!

This year we had a photo booth (with plenty of fancy dress options) and asked our team to tell us why they volunteer. The results were heart warming and are a true demonstration of the passion and enthusiasm in our volunteer team!

Our goal for this event was to make sure every single one of our volunteers was thanked and understood how much they are valued within the organisation. So this blog post is for the members of the team who were unable to make the party.

You are part of the life and soul of Birmingham Museums and we are so grateful for your time. We hope that you enjoy volunteering with us as much as we enjoy having you.

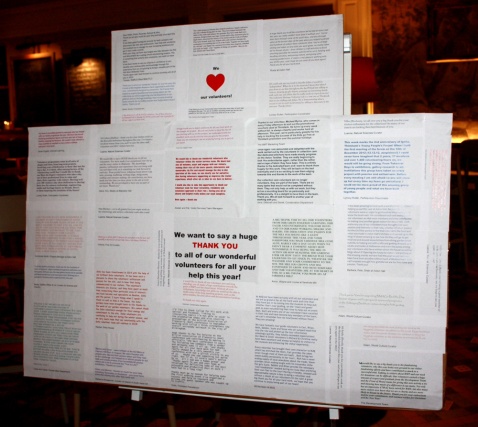

We also created a Thank You Board with messages from staff across the organisation who could not join us on the night. There are so many people at Birmingham Museums who wanted to thank the volunteer team who have made so much possible for us over the course of 2014.

So, to all our wonderful volunteers – thank you for everything you do for us and we look forward to 2015 with you all.

Alex Nicholson-Evans,

Volunteer Development Officer

A Lot of Hot Air

Apart from being one of the most striking architectural features, the gas lights that hang over the Industrial Gallery are an important reminder of the Museum’s roots. They are beautiful to look at and vital to telling the story of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. However, they are also mysterious and we are still trying to find out exactly how they functioned.

This picture shows the Gas lights above the Industrial Gallery during the 1960s. During this period they were not visible from the gallery.

The gas lights have a number of different names. The term ‘Gasoliers’ comes from French ‘chandelier’ and is frequently used in literature about the museum. However, my favourite name is ‘Sun-Light Burners’. This was used to describe them in the minutes made at meetings about opening a gallery. Apart from being vaguely poetic I prefer this term because it accurately reflects their job.

There are seven gas lights in total. Two in the Edwardian Tea Room, three in the Industrial Gallery, one in the Round Room and one above the Vestibule reception area (in every room of the original gallery). They were manufactured by Messrs. Strode and Company from London for the cost of £488.

This is the lamp above the Round Room. I imagine this lamp in particular would have looked like the sun when lit.

The purpose of having gas lights was revolutionary. It reinforces the argument I made in my previous blog entry about how Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery was an institution designed by the people and for the people. In the 1880s Art Galleries were the domain of the middle classes. As well as being a place to see beautiful objects they were also a place to be seen by your peers. Because museums were lit only by sunlight they were only worth visiting during daylight hours. Working class people, generally, did not finish work until the evening and therefore would not be able to see the exhibits.

By providing gas lights Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery enabled these people to view the exhibits too. This explains why the term ‘Sun-Light Burners’ applies so well. The Museum was established specifically to inspire the artisans, therefore it would have been a huge mistake if they could not view the things specifically displayed to inspire them.

When the gallery opened in 1885 it was on top of the newly municipalised city gas offices. Nowadays there are only two things to remind us of this: the Foundation Stone in the main entrance and the gas lamps.

So the practical considerations: how were these lights lit? Naively, when I first considered this question I imagined a Victorian man leaning over the iron work on the balcony of the Industrial Gallery with a large wooden stick, prodding the lamp from a distance and hoping for the best. Obviously, this was not the case. In the case of the lamps above the Vestibule and Round Room, they were winched down to a gentleman below who would light it, shout up to say it was ready, and then be winched up again very early in the morning. It is clear to see that the entire structure would have moved because today they are hidden away in the ceilings. When stood in the roof space this sort of movement is also evident from the design of the lamps themselves.

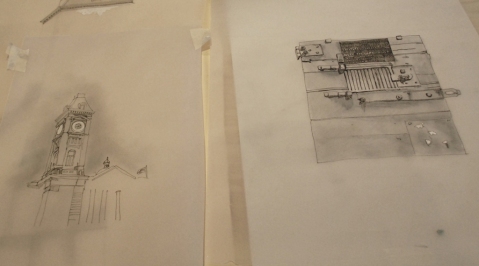

This shows the mechanism used to winch the lamps down so they could be lit.

For the lamps above the Edwardian Tea Room and Industrial Gallery the procedure less obvious. There are winching mechanisms in the roof space but the outer structure of the lamps is clearly static. I am currently waiting to see the original blue prints, which will reveal the procedure but at the moment my best guess is that an internal part was winched down to the floor where it was lit and then brought back up.

The one question we, as Visitor Assistants, always get asked is ‘do they work?’ As the lamps used Town Gas, which is no longer used, it is impossible to tell. Also there are a plethora of conservation issues connected to having gas lamps and oil paintings in immediate proximity so it is probably for the best that we don’t use them today!

So the importance of these architectural features is huge. They remind us of the connection to the gas offices. They are a visual symbol of the equalising effect Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery had on the cities communities when it opened. They also fill everyone who sees them with curiosity and invite questions that we still cannot fully answer.

Olivia Bruton

Visitor Assistant,

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Artist in Residence Jodie Wingham – Week Four

My final week as Artist in Residence at the Museum is now over, the past month has gone so quickly, packed full of new sights, events and meeting new people. During my residency I have been researching pieces within the collections, this research will now be used to create a new piece for BMAG to go on display in January. Continuing with my own practice, interested in the act of looking, the residency has encouraged me to focus on the history behind ‘the gaze’ concerning Women and their image. This is something that became prominent during my research where many of the prints and drawings I looked at depicted women carrying out private acts, often within interior settings, documenting these for the viewer to enjoy. My progress and the ideas behind my new work and its development will be documented by the BMAG team in the coming weeks, please keep an eye out!

I have now moved out of my studio, a space I have made my own during my time here. Not only used as a space for my daily practice I have held workshops for the public and opened it every Wednesday afternoon for visitors to come in and see what I have been up to.

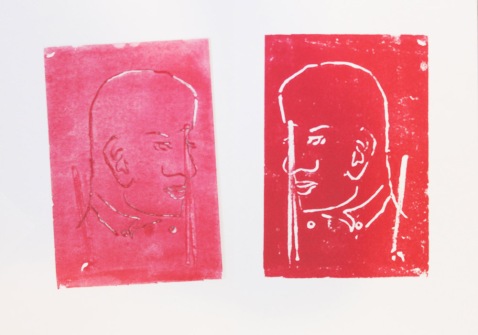

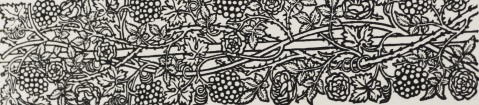

On Friday the 17th of October I held one final printing drop in session, visitors were invited to take inspiration from the woodcut prints of Sir Edward Burne Jones I found in the collections and create their own Lino printed bookmarks.

Here is my own finished bookmark:

It was great fun to help others create something that they could take home and use, everybody enjoyed the Lino method of printing and made some great finished bookmarks.

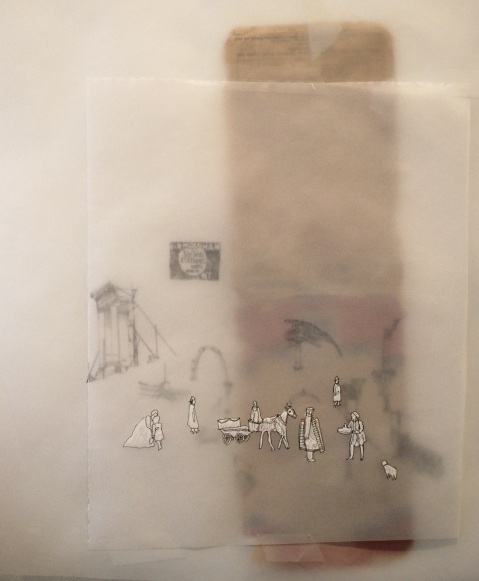

The public facing studio has provided me with a wonderful space suited to my practice, through the glass panel I was able to watch passers by enjoying their visit as well as watching them watch me work. I thought I would play with this idea of the watcher and the watched by covering the glass with semi opaque plastic with peep holes cut away.

I invited the audience to peep through these observing stations to view inside my studio and view myself, in the process photographing this action. It has encouraged me to question the act of looking within a gallery setting, where looking is actively encouraged. This is not limited to the artwork on display alone but it can also be a place to watch other visitors too! I became aware of this within an engraving called The Exhibition at the Royal Academy, 1787 engraved by Pierto Antonio Martini (from the painting by Johann Heinrich Ramberg), where the focus of the viewer is not purely on the gallery display but on the characters themselves within the exhibition.

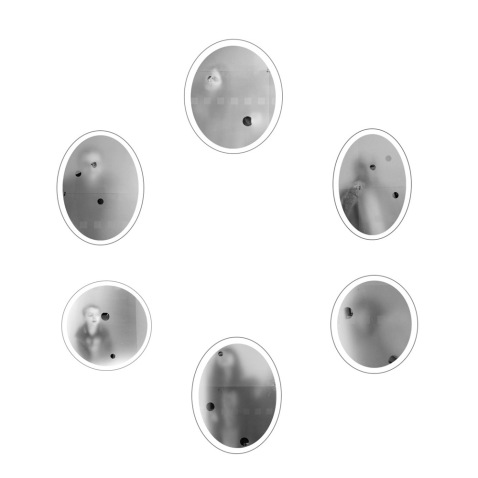

Thank you everyone who participated, here are some images of those who decided to have a peak:

I would like to work with these images further, the blurred outlines of the viewers interests me as you have to fill in the missing information. I have experimented with these few images digitally, as seen below, but I would like to eventually turn them into prints.

Looking through the peep holes visitors could observe me inside my studio:

From outside looking into the studio

I keep returning to this circular shape to frame my images, over the coming weeks I will explore how I can create a sculptural structure that forms this shape on which I hope to print upon. For now, here are some previous experiments into this form:

Finally I want to thank all the staff at BMAG who have given their time generously to view works, arrange events and help me to develop my ideas for this residency to produce a new commission for the Museum. I can’t wait to get started and look forward to its completion.

Jodie Wingham,

Whitworth Wallis Artist in Residence

Artist in Residence Jodie Wingham – Week Three

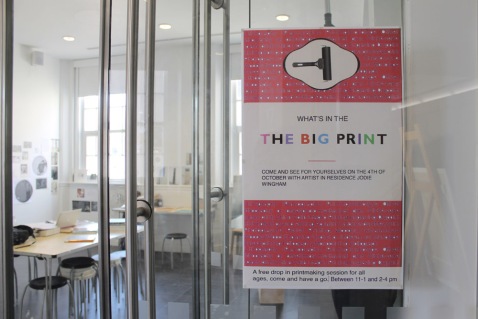

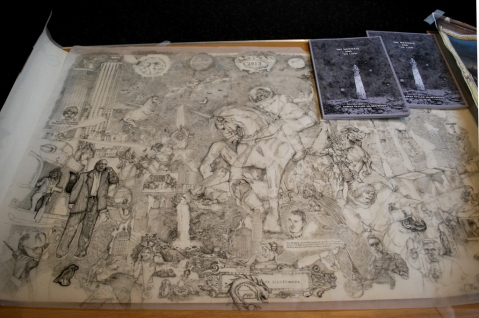

It is my third week at the Museum, and it has been a busy one before I leave on the 17th of October. This week I visited the Museum Collections Centre in Duddeston, home to all the objects not currently on site at Museums across Birmingham, I ran a ‘Big Print’ workshop on the 4th of October in my studio as one of many activities taking place within the Museum as part of Fun Palaces, and I have been working on my ideas for the Final work.

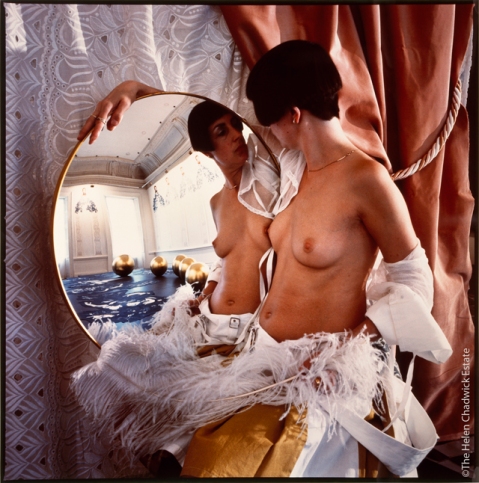

During my time at the Museum I have been carrying out research into pieces held at the Museum to generate a new piece of work in response to what I have seen. Taking inspiration from artists such as Hans Sebald Beham and Helen Chadwick who have used a circular shape within their work, I have been playing with this circular form as a basis to my work. When looking at these artists I became aware of the effect the circular form had on me as a viewer, the shape draws your attention into the image having associations with an old fashioned peep hole of which to view others through.

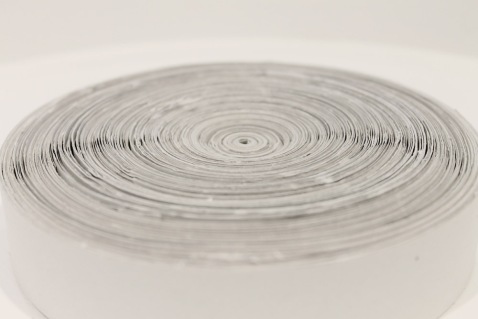

Here is a piece I am working on that incorporates this circular frame:

I have been playing with the use of coiled newsprint paper to form a circular surface on which to screen print upon, I am interested in the distortion of imagery to create a closer inspection from the viewer. During my residency I have seen many images that observe women carrying out certain actions from bathing to changing to sleeping, all private and quite intimate acts however, they are on display for us to observe. It is the subject of women and their image which I think I will focus on as the basis to my piece.

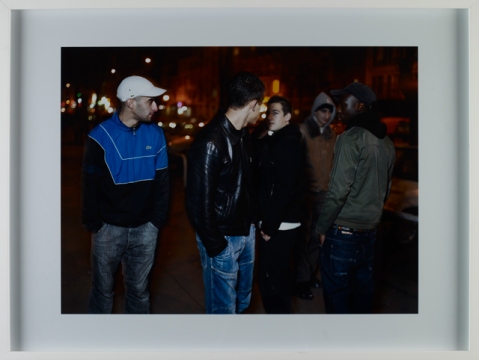

I wanted to learn more about how other artists have used photography within their work to stage certain acts and how they use technology to distort the images they work with. Two artists that do this are Mohammed Bourouissa and Semyon Faibisovich, artists who have pieces held at the Museum Collections Centre (MCC). It was a great opportunity to view the pieces in person and see the techniques used by the artists.

Semyon Faibisovich’s images examine contemporary urban life in his home town of Moscow and particularly the lives of those at the bottom of the social ladder. Using a mobile phone, Faibisovich takes photographs of people on the streets and uses these low resolution images to make his oil paintings, enlarging the images to life size and then painting over the image creating pixelated distortions. This was clear when up close to the works entitled Repose, from At the Stop series, 2009 and Sick on the Way?, 2008 from the same series.

Mohammed Bourouissa is an Algerian photographer who uses staged photography to create images that appear real, often depicting moments of physical or emotional tension through the careful arrangement of people and their gestures. They leave you questioning what has happened in the image or what will happen, I like the suspense he creates leaving you wanting more. I saw La rencontre (The Meeting) and Le toit (The Roof), 2005-2007 during my visit to the MCC and both looked at this tension between the characters depicted.

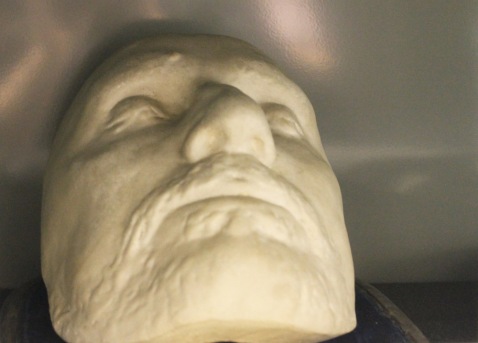

After viewing these specific pieces I spent the rest of my time exploring the vast number of objects and works stored within the centre, it is very easy to get carried away! These are just some of the things I came across:

The Museum Collections Centre (MCC) has a huge natural history collection, with examples of taxidermy ranging from delicate butterflies to a brown bear! Although not relevant to my practical work it was fascinating to see such an array of animals dating back from the 1800’s.

The MCC holds open afternoons for the public on the last Friday of every month and are open for pre-arranged tours and study days, for more information or to make a booking visit: www.bmag.org.uk/Museum-collections-centre.

Finally, thank you to everyone who came to ‘The Big Print’ drop in session to have a taster of what you can achieve through printmaking. From 11-4pm the studio was full of people experimenting with polystyrene prints and mono printing, some fantastic work was made which people could take home or add to the ‘Big Print’ wall in my studio to remain till the end of my residency.

Next week will be my final as artist in residence at BMAG, it has gone so quickly! I am keen to hold one last printing workshop, this time with adults, taking place on Friday the 17th of October between 12.30-2.30pm. We will be making bookmarks inspired by Edward Burne-Jones intricate woodblock patterns I came across in the collections using a Lino print.

Here is one of Edward Burne-Jones’s designs in the collection originally made for the boarder of a book to get you started:

Jodie Wingham,

Whitworth Wallis Artist in Residence

The Sultanganj Buddha 1864-2014

150 years ago today the Sultanganj Buddha, one of the most important objects in Birmingham’s collection, was offered to the Corporation of Birmingham. On 7 October 1864 Samuel Thornton, a former mayor of the city, wrote to Birmingham Borough Council offering:

“…the colossal figure of Buddha, and the large marble one, to the town, to be placed in the Art Museum, now being erected, where they may be duly and properly located for the free inspection of the inhabitants of Birmingham…”

Samuel Thornton’s main business was as a railway ironmonger but he also had an interest in ancient India. Following its discovery by engineers constructing the Indian Railway in 1861, he paid £200 to have the two-metre tall copper Buddha transported to England.

In 1867 the Buddha went on display in the ‘Corporation Art Gallery,’ a room in the Central library. In 1885 it went on display in the newly built Museum and Art Gallery. Today the statue is displayed in the Buddha Gallery. Offerings of flowers are frequently left at the feet of the statue by Buddhist visitors. To commemorate the 150th anniversary, the statue will be blessed by monks from the Birmingham Buddhist Vihara at a public ceremony on Wednesday 8 October between 11am and 1pm.

Adam Jaffer,

Curator of World Cultures

International Women’s Day: Birmingham Women who inspired change

Saturday the 8th March is International Women’s Day.

‘International Women’s Day celebrates the social, political and economic achievements of women while focusing world attention on areas requiring further action.’

In this blog we wanted to highlight the stories of some of the Birmingham women featured in the history galleries who have inspired change.

Ann Fuller

This rare portrait of an18th century businesswoman depicts Ann Fuller who was a pawnbroker in Digbeth during the late 18th century. Ann took over her father’s business at 53 Digbeth shortly after this portrait was painted.

We know very little about Ann other than she was one of a small number of businesswomen in Birmingham at the time. Research for the history galleries revealed other women including Catherine Sawyer who ran the Boarding School in The Square, and Mary Lloyd who was the owner of the Hen & Chicken’s Hotel.

You will find Ann’s portrait in the Strangers Guide to 18th Century Birmingham (1700-1830).

Nellie Hall

Nellie Hall was a suffragette who lived in Edgbaston. She became an active campaigner as a teenager, and suffered imprisonment in Winson Green prison in Birmingham. Later she was sent to prison again in London, went on hunger strike and endured forced feeding. Birmingham had a very strong suffragette movement, which involved women from prominent local families including the Cadburys and the Rylands. The equality for which these women risked their freedom, and sometimes their lives, was a long time in coming. Women over 30 gained the vote in 1918, but full voting equality with men was not granted until 1928.

Nellie Hall wrote to her father from prison in 1914: ‘No free spirit has ever been wrecked by a mean spirited oppression yet. And mine won’t be either.’

You will find Nellie’s hunger strike medal in Forward (1830-1909)

Mary Newill

Stained glass panel in two parts entitled ‘Sleep after Toile’ by Mary Newill, c.1905.

Stained glass panel in two parts entitled ‘Sleep after Toile’ by Mary Newill, c.1905.

Mary Newill studied at the Birmingham School of Art. In the late 19th century the ‘Arts and Crafts’ movement was reviving hand crafts, in a reaction against mass production. The Birmingham School of Art encouraged students to try new techniques, and pioneered art education for women. Female students were encouraged to work with metal, wood and stained glass as well as textiles and painting. Mary Newill was one of the women who forged ahead in techniques traditionally practised by men. Newill also worked as an illustrator and embroiderer, and became a teacher at the School of Art.

You can see Mary Newill’s stained glass panel in Forward (1830-1909)

Lilly Duckham OBE

Lilly was born in Birmingham on the 14 October 1892. She left school aged 14 and went into domestic service. In 1917 she enlisted with the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps aged 25. Lilly was one of 10 women sent to the Western Front to be in charge of the Officer’s catering. Many disapproved of women working on the Western Front. In this extract from an interview with Lilly in 1981 she explained why she believed it was important for her, and other women to serve alongside men.

‘When I read of the quantity of boys that were being killed and that they, they wanted more men they wanted more people out there and they were going to try and experiment with girls you see I put my name through […] They asked if I wanted to stay at home or go abroad, well I very much wanted to go abroad there were only about five of us the rest were wanted to stay in England you know but I wanted to get out […] to do what I could […] I felt that was where the help was wanted was needed and that’s why I thought that’s where we should be and I mean the hardships and everything it was no more I felt it was no more for us than it was for the boys’.

Lilly was demobbed 6 months after the end of the war. Shortly after returning to Birmingham she was awarded an OBE for her war services.

You can listen to extracts from Lilly’s interview as well as other Birmingham women’s first world war stories in An Expanding City (1909-1945) in the Birmingham at War display

Shahin Ashraf

Shahin Ashraf was born in Birmingham in 1971. She is a fundraiser for Islamic Relief, an international aid organisation which began in Birmingham in 1984.

Shahin began volunteering for Islamic relief in 1989 after the Kashmir earthquake. In this extract from her interview for the history galleries she recalls what it was like as a volunteer.

‘We were basically going around the country collecting clothes in a big truck, there was a group of us and we were the only women that could drive at that time. [We then delivered] them back to the warehouse and […] helping […] sorting out clothes, making sure the clothes […] were okay for the country that they were going to. I mean a lot of people gave summer clothes and it was winter there so […] we couldn’t take those clothes’

Islamic Relief [was] in its infancy and then what happened was that […] Central News in Birmingham […] picked it up and suddenly there was an influx of clothes and the warehouse was full to the brim but they had […] hardly any volunteers

So this was the call for volunteers and I was one of the very few volunteers. In those days there was no texts, there no sms, there was no email, it was just word of mouth and Doctor Hany [the founder of Islamic Relief] had gone to the different colleges within Birmingham and he said I really need your help so if you could come to the warehouse […] and suddenly there was about 4-500 volunteers’.

You can listen to extracts from Shahin’s interview in Your Birmingham (1945-today)

Jo-Ann Curtis and Henrietta Lockhart, Curators – History

Half Term at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

We are getting ready for what will hopefully be a very busy holiday week at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. Our theme this half term is Animals and there will be lots for families to see and do.

Every day of half term (17th-21st February) we have two exciting drop in activities taking place:

- In the Learning Zone you can meet some amazing real animals from Animalmania, the mobile zoo (on 18th and 21st) and the Minibeast Roadshow (on 17th, 19th and 20th) between 11am-1pm and 2pm-4pm each day. You can even hold some of them if you are feeling brave enough! (£1 per person)

- In the Activity Zone families can work with local artist Lucy Read to make and decorate their own animal puppets (on 17th, 19th and 21st) or bearded dragon character to take home (on 18th and 20th), between 11am-1pm and 2pm-4pm, daily. These activities are designed for families to take part in together and all ages are welcome. (£1 per child)

You can also pick up a copy of our free Animals in Art trail from the animal handling activities or from the vestibule reception desk.

We also have two hour artist led workshops for children looking for a more in depth activity and to improve their artistic skills (on 19th and 20th Feb). Please book online in advance for this session (morning or afternoon workshops available). £5 per child, suitable for ages 7 and over.

For further details of events and activities for families across all of Birmingham Museums sites please visit www.bmag.org.uk/events

(Please note that children must be supervised by a responsible adult at all times.)

Sarah Walker

Informal Learning Officer

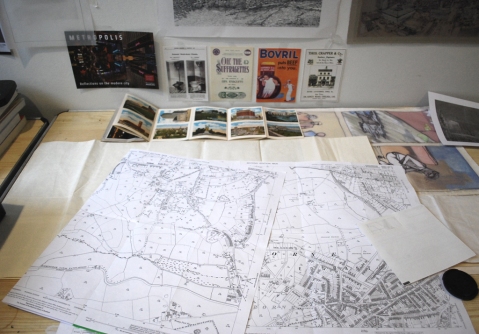

Artist in Residence Sarah Taylor Silverwood – Week 4

I have spent the last month researching the collections during my residency here. I have now finished at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG) and moved back into my studio. I’ll be channelling these ideas into a new commission for BMAG for January. The residency has encouraged a new direction for my work, where my public facing studio encouraged conversations and interactions with staff and the public. These daily conversations have fed into my artistic process and encouraged me to rethink my relationship with ‘the gallery’, and the editing process that I go through while making work. It has also given me an insight into the direct art historical context of the materials I use, and how drawing and works on paper have been used.

The studio itself has been a significant influence on how I’ve been working.

The view looks out onto Victoria Square and Town Hall.

The space has been used for both workshops with the public and my daily studio practice.

These sketches are the beginning of the exploration into my new work, which evoke familiar motifs of journeys, place, and landscape.

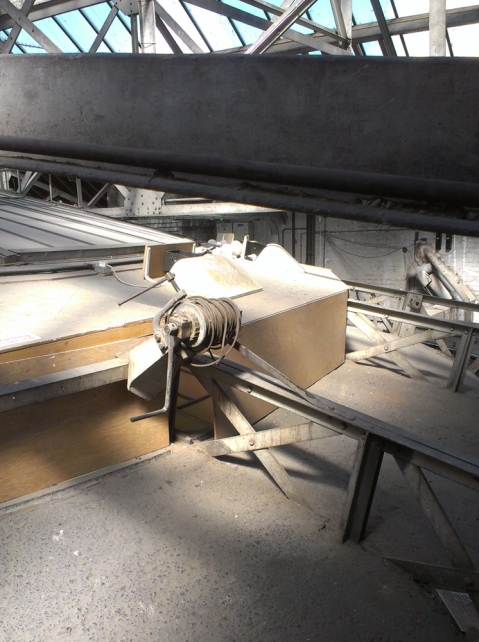

During my time here, I have looked at a huge range of landscapes and topographical views in the collection. I also spent some time with photographer David Rowan, who showed me the work he had done documenting the view from the roof of the building, and also how the roof and dome at BMAG have gradually been restored. This has pushed me to think more about the importance of viewpoints within a changing city.

I keep coming back to this painting within the collection, titled ‘Birmingham from the Dome of St. Philips Church’, painted by Samuel Lines in 1821 (the church is now a cathedral).

It was made from the dome, which is inaccessible to the public now. The dome was then the highest point in the town, and still seems very high – it is said to be the same level as the cross on St Paul’s Cathedral in London. It is a fascinating perspective on the city and I was captivated by the idea of recreating this view today.

This week I met with Catherine Ogle (Dean of Birmingham) and Rob Hands (Head Verger at St Philip’s). Rob and I climbed the precarious tower to the top of the dome, then compared the views. Thanks to a compass and a selection of historical maps, I worked out the angle from which Samuel Lines created his painting. The original painting was made pointing southwest – I overlaid old and new maps to give a rough idea of the angle.

I will be spending the coming weeks exploring the idea of this view, or ‘prospect’, and its historical and cultural significance. The BMAG team will be documenting my new commission and its development. For now, here is a view of the clock from inside the tower and the gravestone of Samuel Lines himself, in the graveyard of the Cathedral.

I’d also like to add a huge thank you to all the staff at BMAG who have been generous with their time and resources to help me develop this residency and commission.

Sarah Taylor Silverwood,

Whitworth Wallis Artist in Residence

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery History Project

My name is Olivia and I work as a Visitor Assistant at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG). It is impossible to work in such a beautiful building without being curious about its history.

In May 2012 three colleagues and I began to research specific areas of interest as part of an ongoing project to discover, and make available, more information about an institution that is over 127 years old.

Rachael Yardley focuses primarily on the architecture of the building, Helen Roberts researches the people who were of vital importance to BMAG and Tomasz Kolisko’s area of interest is the collection itself. I have been engaged in the social and political history behind the museum’s foundation and development.

In this blog I intend to share the process of research we went through to get to the stage we are currently at, as well as keeping you up to date with any further developments.

This photo is a front cover of a BMAG publication that held information about up and coming events in the Gallery, from 1980. It shows a drawing of the Museum from the outside in the nineteenth century when it first opened – before the bridge extension was built.

‘The History of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery’ is such a huge subject that even after splitting it into sections it still took the better part of a year to get to a stage where we all felt we had a good enough grasp of the topic to give a presentation to other departments in the museum. When the four of us first sat down to discuss the project, over copious cups of coffee, we had no idea of how consuming the research would be.

The first problem we encountered was where to start. We decided to simply wander around the museum asking colleagues for anecdotes or just quizzing them on everything they knew about the place they worked. However, this method proved incredibly problematic because all too often one of us would run to another with an interesting revelation only to be told “That’s not what I heard.” Clearly this wasn’t working. Too many ‘facts’ we got told were ‘certain’ directly contradicted others.

It would be impossible to undertake the project without first consulting Stuart Davis’ book “By the Gains of Industry: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery 1885-1895”. This was easily accessible in the Museum shop and gave us a much better platform to start from (not least because it has a list of sources). However, in places it was slightly confusing and I found myself with a long list of citations with question marks next to them – a recurring theme. The next stage was obviously to turn to Davis’ sources and finally we felt we were getting somewhere. But books proved few and far between on the topic of the BMAG’s history.

The Inscription (or Foundation) Stone can be seen in the main entrance of the Museum. It is the first stone that was laid in the building on 19th July 1881 by Mayor Richard Chamberlain. It also includes the Museum motto ‘By the gains of Industry we promote Art’.

A few months into the project we realised we had foolishly ignored something very obvious. BMAG is full of plaques revealing the important benefactors and gallery openings. The first two items to enter the collection are still on display; the Bust of David Cox and the Sultangani Buddha. The museum walls gave us yet more dates and names to bounce around the internet.

The internet proved to be the worse source of all. The digital world appeared to be almost a complete void of information regarding the history of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, aside from what was written on BMAG’s website. I even tried university journals to very little avail.

My pet peeve for those first few months was my inability to locate a concise list of previous directors anywhere. On the advice of Martin Ellis (Applied Art Curator) I spent a long and cold afternoon in the archive section of Central Library working my way through the volumes of ‘Who’s Who in Birmingham’ from the 1890s-1997. Usually pages 44-45 held a brief overview of the Museum and Art Gallery with the Keeper or Director’s name and a few details about what departments we had. There were two shelves within the date range I needed and I was reluctant to miss out a year just in case there was a Keeper or Director who only worked there for one year.

I left the library with a scrap of paper listing 6 names, 10 dates and 2 question marks – and a sense of achievement.

This is a photograph of the Vestibule. Unfortunately we do not have an exact date for it yet but we think it was taken in the very early twentieth century.

When we discovered the Social History Library within the museum itself the project finally took flight. We found boxes of photographs revealing the museum in the 1890s and the building of the extension in the early 1900s. A bit of detective work and was required to attribute dates to some of them. We uncovered old exhibition catalogues, newspaper cuttings, visitor reports, and meeting minutes. We also found a very helpful ghost unless the curators were playing tricks on us. Each time we discussed needing to find out something specific we would return to the library and magically it would appear. We would discover new photographs in boxes we were certain we had seen everything in before. Also, things we remembered seeing would mysteriously disappear one day and reappear a week later. We discovered biographies of all the important benefactors to the Museum and Art Gallery and huge catalogues of the collection hidden away in the darkest corner.

This photograph is from above the Industial Gallery when it was boxed in after the Second World War, however, we are not certain of the date.

Over eight months we pieced together a document that aims to provide answers to most questions we, and visitors, have about the history of the building. These include: why it was built, where the funding came from, who designed it, how we came about the collection and who made it all possible. Most importantly we discovered an immense passion for the place we work. We presented our findings in a full staff briefing and were stunned to see our level of excitement and curiosity mirrored in our audience.

The research is, of course, ongoing. We still have broad questions and assumptions we need to prove. We each have very specific areas of interest that we are independently studying and sharing so hopefully the project will expand further and future employees and visitors will have an easily accessible information about the Museum and Art Gallery.

This is another cover from Gallery News from 1982. It shows the Industrial Gallery before the staircase was put in place which dates it between 1885-1890.

We have just begun to give guided tours for the public at £3 per person. The next one is on the 23th of July at 1pm – for more details please visit BMAG’s What’s On page.

Olivia Bruton

Visitor Assistant at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery